- Published: 3 January 2017

- ISBN: 9780143782032

- Imprint: Bantam Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 320

- RRP: $37.00

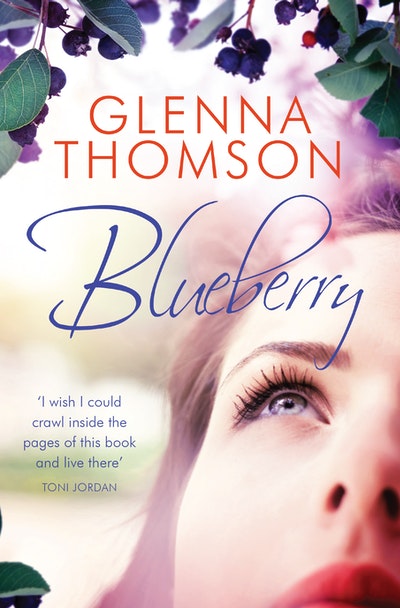

Blueberry

Extract

When I left the apartment it was early dusk, that perfect moment when the light appears mauve. I loved this time of day, although I was often indoors and missed it. Someone had dropped a pizza box on the ground near the Japanese maple, red leaves had fallen inside. I looked up to my window – the curtain was still open but the light was now on. But it was all right to leave, so I turned away.

Along the footpath, a fit-looking man in his mid-fifties wearing a dark suit waved at me. He watched me approach and opened the back door of a car in sync with my arrival. Michael was waiting for me on the far side of the backseat, looking like he usually did – serious and slightly preoccupied. The radio was on and a football commentator was raving over the noise of the crowd.

I slid in and the door closed.

We kissed, a light touch, and when I buckled my seatbelt he felt far away, like we were anonymous travellers, strangers.

‘Which team do you follow?’ he said.

‘I don’t.’

‘Really? A Melbourne girl who doesn’t follow footy?’

‘That’s me.’

The driver started the car.

‘This is Neil.’

Neil’s eyes were in the rear-vision mirror. We nodded.

‘Do you drive much yourself?’ I asked.

‘Not at the moment.’

The footy was distracting. And Michael was distracted by it, his ear half-turned, listening to the game while he was talking.

‘Why’s that?’

He shook his head as if denying something. ‘Over the limit. It’ll right itself in a few months.’

He reached for my hand and every now and again gently rubbed his thumb on my palm as if to reassure me I was not forgotten.

Neil drove us down Birdwood Avenue, beside The Tan. Even at that hour on a Saturday night, joggers were out. Sunset was coming fast, the sky now streaked pink, silver and grey.

Along St Kilda Road, we crossed the bridge and sat behind a tram. Passengers stepped off, others got on. Michael’s profile was backlit against the side window. There was a squint in his forward gaze as he concentrated on the game. His grey suit was fine wool, perhaps cashmere, worn with a black open-neck shirt. He was particular with his grooming, much more than the other corporate types I worked with. Michael was the new head of Wrens Asia, the global food giant with brands in almost every category – frozen and canned meals, cereals, bread, sauces and condiments, and infant foods. The account wasn’t exciting, but Michael somehow brought people to him. Perhaps his positional power was the attraction. He was always full of big and new ideas; his staff fawned over him. The food industry couldn’t get enough of him – his calendar was booked for months ahead with appearances and speeches.

His popularity made me curious, and wary. I wasn’t sure about him. If anything, at times I found he could be overbearing and egotistical. Even so, the decision to accept his invitation to dinner was simple – his persistence was too hard to resist. And Jane, my best friend, was all over it, insisting I go.

Michael turned and smiled. I looked at his pale skin and perfect teeth. He wasn’t unattractive.

Into Little Collins Street and I guessed we were going to McKay & Co. I had been there only a fortnight earlier for lunch with my banking client to celebrate the launch of their new private equity brand. Neil opened my door and watched me shuffle out, wrestling with my skirt.

Inside, the maître d’ hurried towards Michael with his hands out in front, calling us to follow. We were seated close to the front kitchen, a bar-height stainless-steel-and-glass bench where a dozen white-clad young male chefs worked furiously with their heads down. After the water was poured we were left alone to feel the pause, that awkward moment looking around and thinking what to say. I hadn’t been on a date for a long time – more than twelve years if being in a long-term relationship didn’t count.

‘We’re having the set menu,’ he said.

I settled into my seat.

From inside his jacket came the bleep of a message. He reached for his phone, read it and grinned. I was already smiling back at him, as if I knew the news, or cared.

‘Dockers are up nineteen points.’

The first course was Tasmanian trout and cured eel with organic rocket, served on a hot stone slab. The sommelier poured a short glass of riesling.

Michael ate thoughtfully, then dabbed his mouth with a napkin and told me that just last month he had been to Tasmania and MONA.

‘Have you been there?’

‘Hobart, yes. MONA, no.’

He sat back and swirled and sipped his wine as he described a mechanical stomach that was fed each day. I was leaning towards him, taking it all in – his impressions and the sense he hadn’t been there alone. That bothered me, but I didn’t ask. I knew he’d been married and had a son named William.

The next course was neatly served, pork with thyme noodles. He held up his fork, a wet yellow worm dangling from it, and turned it slowly, studying it. ‘You know, our R and D people in Singapore have come up with a healthy noodle. Air-dried, low fat. Nice biscuit taste.’

I was about to ask a question when his pocket sounded with another incoming text. He pulled out his phone and read the message.

He clenched his fist in victory.

‘It’s a good night. Dockers have won and I’m here with you.’

We clinked glasses and tasted the wine.

Another course was delivered: trout-and-mandarin soufflé in a bowl not much bigger than an eggcup. I told him my father had been a devoted trout fly-fisherman and that by the age of eight I’d mastered all the knots and could tie them faster than my brother.

‘. . . my favourite was the Albright, which is the hardest.’

He listened with his eyebrows raised as if waiting for the punch line – and when he realised it was just a pointless story there was a pause, a subtle withdrawal. I picked up my glass and looked around. The restaurant was full, with hushed conversation at each table. Michael shifted in his chair and started talking about an online portal for packaging ideas from employees and the public. Someone had already sent in an idea for a resealable pouch and won a thousand dollars.

‘It’s a good idea, don’t you think?’ he asked.

The way his mouth moved as he spoke, the line of his neck and shoulders. I was watching him talk, not quite listening, trying to decide if I liked him. Perhaps I could adapt to him? But love wasn’t about adapting. Or maybe it was. I didn’t know. He was staring at me.

‘You know, I like you very much,’ he said.

‘I’m glad.’

‘You seem shy. I wasn’t expecting that.’

And there I was, smiling like a stupid girl with a crush.

He reached across the table for my hand and I met him beside the salt, a dry, soft touch.

Dessert arrived. The lavender ice-cream got him talking about a Wrens innovation in soft-serve vending machines. I felt a lag in my thinking, like I’d been in a meeting that was going on too long. My hand kept reaching for the wine of its own accord and not the water and when he finally ordered coffee, I felt relieved.

Out on the street, I breathed in the chilly air.

Neil was waiting on the pavement. The back door was already open.

We drove back to my apartment in silence. People were on the streets. Fed Square was lit purple. Cabs queued at the station. Cars and trams choked St Kilda Road. Michael’s arm was stretched out, his hand was on my thigh.

The old oaks along my street were shedding red, gold and brown leaves, some as big as dinner plates – an artist’s work on the footpath. Neil pulled into the apartment car park and Michael got out and opened my door. It was cold and I shrugged into my coat.

‘Can I tell Neil to come back for me in the morning?’ he asked, putting his arm firmly around me, like he belonged, like we were a couple.

Beyond the dim car park was the black night, no stars or moon. Apart from the lovely feeling of being held, there was nothing romantic about where we were standing.

He lifted my chin and kissed me tenderly.

Of course, I knew I should send him away. But maybe it was time to let go, to move on. And there it was – a simple thought about being free, taking a risk and not caring so much.

I nodded.

Michael went to the driver window.

Neil started the motor. He had turned onto Toorak Road before we’d taken our first carpeted step up to the second floor.

Blueberry Glenna Thomson

Blueberry is a heart-warming debut novel about starting over, as a little blueberry orchard in the hills offers one woman the chance to change her life forever...

Buy now