- Published: 1 March 2012

- ISBN: 9781864712308

- Imprint: Bantam Australia

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 464

- RRP: $24.99

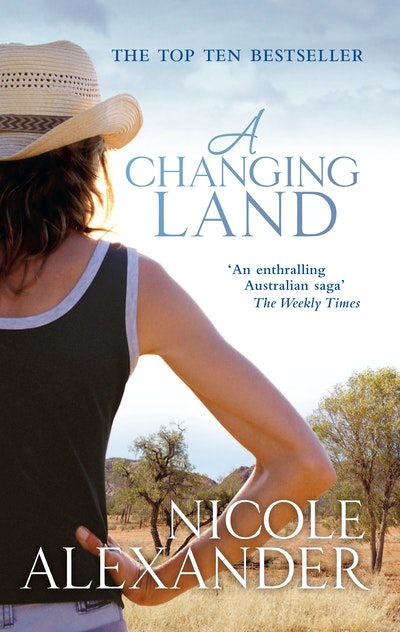

A Changing Land

Extract

Autumn,

1989 Wangallon Station

Forty emus raced across the road, their long legs stretching out from beneath thickly feathered bodies as their small erect heads fastened on the fence line some five hundred metres away.

Sarah couldn’t resist going up a gear on the quad bike. She pressed her right thumb down firmly on the accelerator lever and leant into the rushing wind. Bullet, her part-kelpie, part-blue cattle dog, pushed up tight against her back, squirrelling sideways until his head was tucked under her armpit. She swerved off the dirt road in pursuit of the emus, the bike tipping precariously to one side before righting itself. A jolt went through her spine as the quad tyres hit rough ground. Then the bike was airborne.

Bullet lost his balance on landing. He gave a warning yelp as Sarah grabbed at his thick leather collar, managing to drag him up onto her lap. Despite the urge to go faster, she slowed the bike down, the brown blur of feathers dodging trees and scrub to outrun her. Sarah loved emus, but not the damage they did to fences or the crops they trampled. Chasing them off Wangallon, albeit onto a neighbouring property, seemed a better alternative to breaking their eggs in the nest to cull numbers. She poked along slowly on the quad until she reached the fence. A number of emus had managed to push their prehistoric bodies through the wires, while the rest ran up and down the boundary trying to find a way out. Bullet whimpered. Sarah reached the fence as the last of the mob disappeared into the scrub, scattering merino sheep in their wake.

‘Sorry.’ Sarah apologised as the dog jumped from the bike, turning to stare at her. Bullet never had gone much on losing his footing and it was clear Sarah would not be forgiven quickly. He walked over to the nearest tree and lay down in protest.

Two bottom wires on the fence were broken and the telltale signs of snagged wool and emu feathers on the third wire suggested this wasn’t a recent break. Sarah walked along the fence, stepping over fallen branches, clumps of galvanized burr and a massive ants’ nest of mounded earth a good three feet in height. Eventually she located the two lengths of wire that had sprung back on breaking. Taking the bottom wire she tugged at it and threaded it through the holes on the iron fence posts until she was back near the original break. She did the same with the second wire and then walked back to the quad bike where an old plastic milk crate was secured with rope. Inside sat a pair of pliers and the fence strainers. Grabbing the tools, Sarah cut a couple of feet off the bottom wire, then interlaced it with the freshly cut piece until it looked like a rough figure eight. She pulled on it, feeling the strain in her back, until it tightened into a secure join, then she attached the strainers and pulled back and forwards on the lever. The action tightened the wire gradually. Once taut, Sarah used the pliers to join the ends. More wire was needed to repair the bottom run but at least it would baulk any more sheep from escaping.

Whistling to Bullet to rejoin her, Sarah followed the fence for some distance on the quad before cutting across the paddock. Little winter herbage could be seen between the tufts of grass. The rain long hoped for in March and April had not arrived and May was also proving to be a dry month. It was disappointing considering the rain which had fallen in early February. Within ten days of receiving nearly six inches, there was a great body of feed and then four weeks later, with a late heatwave of 42 degree days, the heavy grass cover sucked the land dry and the feed that would have easily carried their stock through a cold winter began to die off.

The pattern of the next few months was trailing out before her like a dusty road. In one month they may have to begin supplementing the cattle with feed; in two they may have to be feeding the sheep corn. By mid-July they would begin the search for agistment or perhaps place a couple of mobs of cattle on the stock route.

Mice, lizards, bush quail and insects all disturbed into movement by her bike created a sporadic pattern of scampering life amid the tufts of grass. A flat expanse of open country lay ahead, punctuated occasionally by the encompassing arms of the wilga and box trees that dominated the landscape here. Ahead, the edge of a ridge was just visible; a hazy blur of distance and heat shimmering like an island. Soon the rich black soil began to be replaced by a sandier composition, the number of trees increasing, as did the birdsong.

The midmorning sunlight streamed into the woody stand of plants, highlighting saplings growing haphazardly along its edges. They were like wayward children, some scraggly and awkward in appearance, others plump and fresh with youth. Sarah drove the quad slowly, picking her way through the ridge, passing wildflowers and white flowering cacti. The trees thickening as she advanced deeper. The air grew cooler, birds fluttered and called out; the cloying scent of a fox wafted on the breeze. The path grew sandy and the quad’s tyre tracks became indistinct as the edges collapsed in the dirt. Above, the dense canopy obliterated any speck of the blue sky.

Sarah halted in the small clearing. The tang of plant life untouched by the sun’s rays filled the pine-tree-bordered enclosure. She breathed deeply, revelling in the musky solitude. Through the trees on her right were the remains of the old sawpit. The pale green paint of a steam engine from the 1920s could just be seen. It was here that her grandfather Angus had cut the long lengths of pine used to build the two station-hand cottages on Wangallon’s western boundary. The sawpit, long since abandoned, also marked the original entrance to Wangallon Station. Long before gazetted roads and motor vehicles decided the paths that man could take, horses, drays and carriages bumped through this winding section of the property, straight through the ridge towards Wangallon Town.

Sarah continued onwards. Soon the tall pines began to thin out, the air lost its cool caress and within minutes a glimpse of sky gradually widened to a view of open country. She weaved away from the ridge through a tangle of closely growing black wattle trees and belahs, the thin branches whipping against her face.

She was in the start of the swamp country where a large paddock was cut by the twisting Wangallon River in one corner. The area was defined by scattered trees and bone-jarringly uneven ground. A ridge ran through the paddock and it was here that sandalwood stumps spiked upwards from the ground. Sarah stopped the bike and alighted.

Years had passed since she’d last been in this area alone. It was almost impossible to believe that her beloved brother had died here in her arms over seven years ago. Kneeling, Sarah touched the ground, her fingers kneading the soft soil.

In snatches the accident came back to her. His ankle trapped in the stirrup, his hands frantically clawing at the rushing ground, and then the sickening crunch as he struck the fallen log and the spear-like sandalwood stump pierced his stomach. Sarah swiped at the tears on her cheeks, her breathing laboured. Closing her eyes she heard the shallow rasp of his breath, like the rush of wind through wavering grasses.

Anthony caught up with her a kilometre from Wangallon Homestead. Sarah could tell by the lack of shadow on the ground that she was late. His welcome figure drew closer, just as it had when he had come searching for her and Cameron all those years ago. At the sight of him the tightness across her chest eased. As the white Landcruiser pulled up alongside her quad Sarah leant towards him for a kiss. Her forefinger traced the inverted crescent-shaped scar on his cheek, the end of which tapered into the tail of a question mark. Sometimes the eight years since his arrival at Wangallon only seemed a heartbeat ago.

‘You’re late,’ Anthony admonished.

Sarah sat back squarely on the quad seat. So much for the welcome.

‘I was worried. What’s with all these long rides around the property?’

‘It’s his birthday.’

‘Oh.’ Each passing year Cameron faded a little more from Anthony’s memory. He gave what he hoped was an understanding nod. ‘Been fencing?’ he nodded towards the milk crate. ‘You don’t have to do that stuff you know, Sarah.’

If she expected a few words of comfort, Anthony was not the person to rely on. He rarely delved past the necessary. She gave a weak smile. ‘I am capable of fixing a few wires.’

‘I don’t want you to hurt yourself,’ Anthony replied with a slight hint of annoyance. ‘And what’s with taking off and not letting me know where you’re going or how long you’ll be away?’

‘Sorry.’

He scratched his forehead, the action tipping his akubra onto the back of his head. ‘Well, no harm done. Let’s go back to the house and have a coffee.’

‘Would that be a flat white? Latte? Espresso?’

Anthony rolled his eyes. ‘How about Nescafé?’

Bullet barked loudly. ‘Sounds good.’ Sarah pushed her hat down on her head and sped off down the dirt road with Bullet’s back squarely against hers. She slowed when they passed some Hereford cows grazing close to the road. ‘G’day girls,’ she called above the bike’s engine. Bullet whimpered over her shoulder and gave a single bark as they crossed one of the many bore drains feeding their land with water. These open channels provided a maze of life for Wangallon’s stock and Sarah never failed to wonder at the effort gone into their construction nearly a century ago under the watchful command of her great-grandfather Hamish. Shifting up a gear, she raced through the homestead paddock gate to speed past the massive iron workshed and the machinery shed with its four quad-runners, three motorbikes, Landcruisers and mobile mechanic’s truck. Weaving through the remaining trees of their ancient orchard, Sarah braked in a spurt of dirt outside Wangallon Homestead. She smiled, watching as Bullet walked through the open back gate, pausing to look over his shoulder at her.

‘I’m coming.’

Bullet spiked his ears, lifted his tail and walked on ahead.

A Changing Land Nicole Alexander

A bestselling rural novel from the 'heart of Australian storytelling' Nicole Alexander. A Changing Land tells of one woman's fight to keep the farm that has been in her family for generations.

Buy now