- Published: 3 November 2020

- ISBN: 9780143774228

- Imprint: RHNZ Godwit

- Format: Hardback

- Pages: 160

- RRP: $75.00

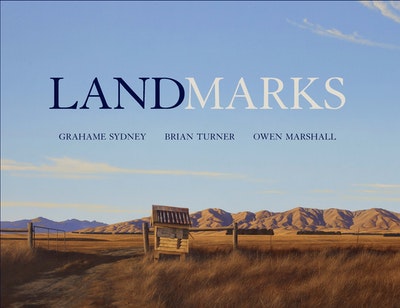

Landmarks

Extract

FOREWORD

Fiona Farrell

Twenty-Five years ago, Sam Neill wrote the introduction to this book’s predecessor, Timeless Land. In it he described with great warmth his attachment to Central Otago, beginning with childhood camping trips: the old Bedford van chuntering up one of the several routes from Dunedin, the puking of children in the back seat, the tussock country, the rivers and lakes, the unwieldy tent, his dad’s baggy ex-army khaki shorts . . .

I recognise those shorts. My dad had them too. There’s a photo of him standing by the old railway wagon the Waitaki Electric Power Board social club had transformed into a crib at Hakataramea. A few working bees, a lean-to for the double bed, a bunkroom for the kids. In the photo he looks happy, as he always did when he was outside in the sunshine. He’d served in the desert and loved the heat.

We are standing in front, my cousin Pat holding a home-made cricket bat, me holding the ball, and my little sister guarding the apple box we used as a wicket. We all look a bit dishevelled, with sticky hair, bare feet. The photo is black and white, but you can tell the grass is summer brown, and off to the right there are willows lining the banks of the river flowing fast and shallow over shingle, pooling abruptly around big rocks as icy deep swimming holes. There’s the feeling of being somewhere secret. There’s the memory of arrival, the tiny red Standard packed to the gills with bedding and cartons and cake tins and us squashed and squabbling in the back seat all the way up the Waitaki valley from Oamaru. Rattling across the wooden bridge at Kurow, up and over the hill and down into the valley concealed between the Kirklistons to one side and the Hunters Hills on the other. There are sound effects: sheep bleat, magpie gargle, the wind rustling in willow leaf.

What isn’t in the photo is what came next. A day or two later, my dad put on his equally embarrassing togs and dived into the swimming hole, and collapsed. My mother, four foot ten but strong, dragged him out. He spent the rest of that holiday in bed. He had been wounded at Alamein and the shock of that icy water triggered acute arthritis. Within a few months he was in callipers, barely able to move. He remained that way for the next twenty-five years.

Places are like that. A mix of sensation. There is beauty. There is happiness. But nothing is truly ‘timeless’. Change and entropy are the laws we live by.

I was born in the south, the region shared by the three men who have created this book. Brian Turner has written poems about it, Grahame Sydney has painted its bare landscapes, and Owen Marshall’s stories populate that landscape with a cast of characters whose quiet laconic demeanour as often as not conceals deep passions.

Up close of course, ‘the south’ is a whole lot more complicated than that. Like every part of this country it is a marquetry of tiny independent states between narrowly defined borders.

The Waitaki marks the northern boundary with the glory of milky- blue snow melt surging down to the Pacific from the Main Divide. On its southern bank there are the limestone outcroppings of North Otago. Tiny muddy creeks wriggle at the foot of ancient reefs, carved by wind and rain to fantastical shapes, caverns, dragons, and there’s the dry rattle of cabbage trees, tī kōuka, and the tangle of matagouri. Further south, towards Dunedin, there are the big rounded basalt domes of an earlier, fiery era. Their molten slopes are smoothed now and prickly with Spaniard, which might belong to the carrot family but has long since given up on being a carrot, left home and joined a tougher gang. There’s damp green bush in gullies and every little bay along coast and peninsula works its own vari- ation of volcanic rock, cockle-rich sediment and white sand that squeaks under your feet as you walk, alone, on the windswept miles.

Should you decide to turn west, your road will rise up before you until the country opens out with the suddenness of revelation. There are rolling brown hills that once rippled with tussock like an inland sea. An immense blue sky across which sail white clouds, some as thick, round and luminous as if they carried crews of alien beings. Schist begins to punch through the sheep-nibbled ground, sculpted into towers and standing forms that demand veneration and in other times might have received it.

The land up here is folded. The Pisa Range, the Dunstan, Raggedy, Rough Ridge, Rock and Pillar form rows in parallel as they are being thrust up, by the immense forces at their constant grinding work beneath our feet, into the sunlight. You pass between them, skylarks rising on thin columns of song, hawks slung from a thread, noting with their bright black eyes the tiniest movement of mouse or sun-warmed lizard. You revel in the sensation of immense space, with so much room to breathe. Your body expands in that wonderful mysterious way it can, to take in cloud and mountains in summer brown or winter snow or the chill white stillness of hoar frost making rococo ornament of fence wire and telegraph poles.

And each valley, each hilltop is its own region, subject to its own angles of wind and rain and sunlight, and beyond them lie the lakes and the yahoo of Queenstown and the big silent mountains of the Main Divide, just waiting their moment to jump into new configurations, because this is not and never has been truly a ‘timeless land’.

It changes, just as the authors of this book have changed. These men are 25 years older than the men in the author photographs in the original volume. At a quick glance nothing may seem to have changed. Sydney’s paintings still stretch amply across the wide pages with their low horizons, their solitary tree or sheep yard alone in immense space. Turner’s hawks still hover, his rivers still run, and Marshall’s characters still move about the landscape, filled with longing and unexpressed love. But change has been at work.

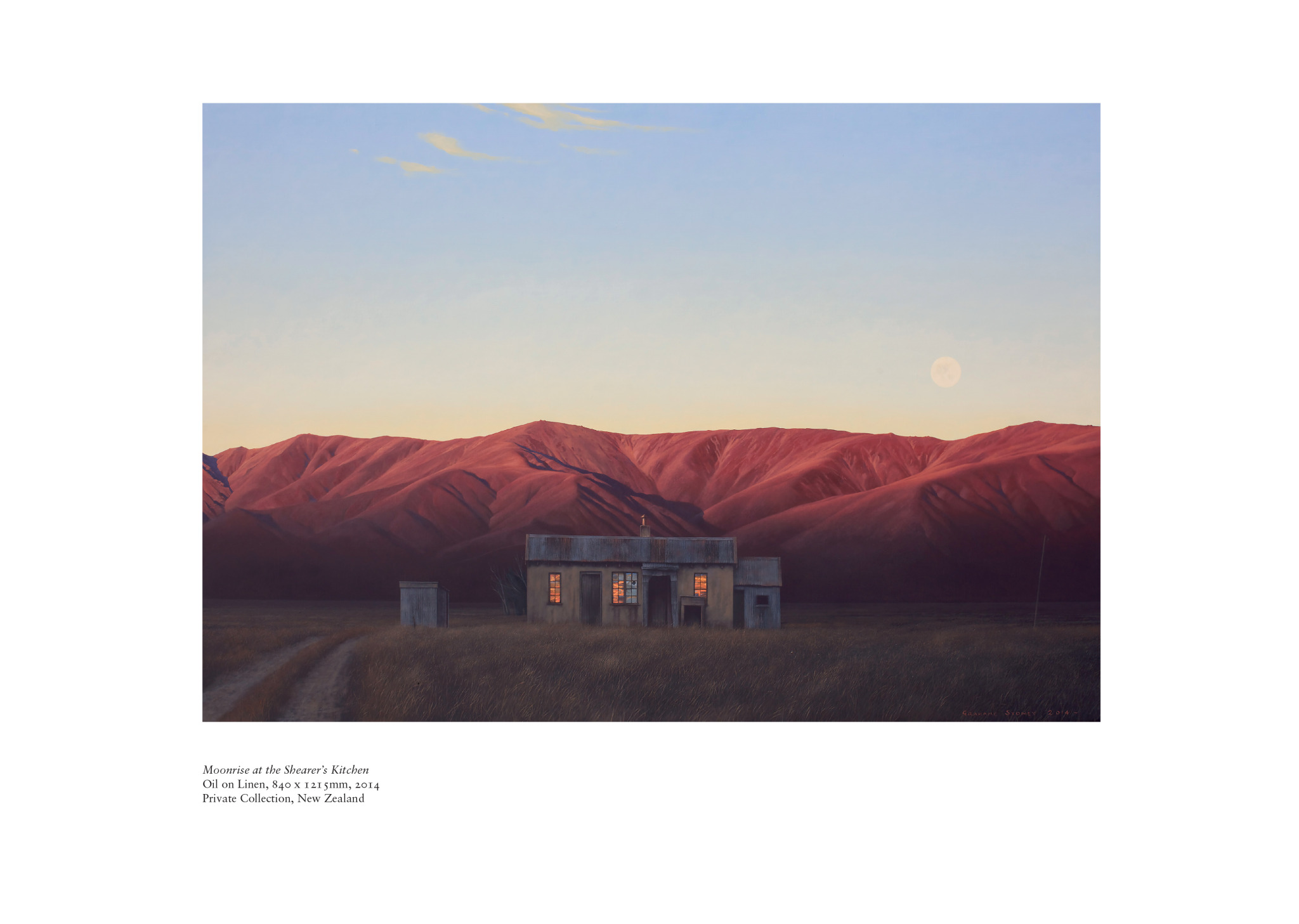

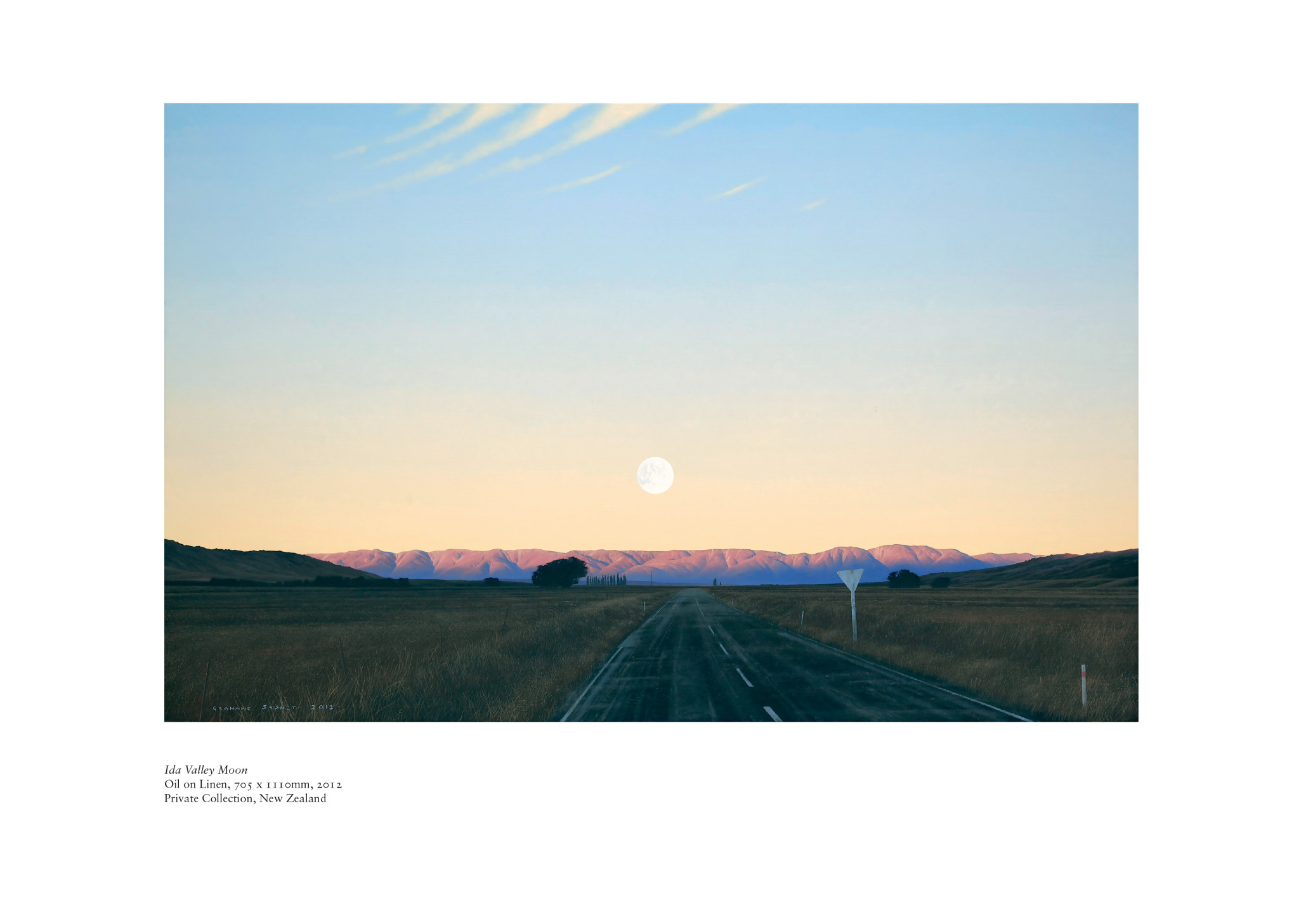

Sydney’s paintings in this collection are often set at twilight, or at night, the gathering darkness lit only by a pale moon. Turner’s poems have taken on a political edge, lamenting the loss of rivers to the filthy tide of intensive dairying and incessant land modification. Marshall’s stories have an elegiac ring, in the gentle longing, for example, for that boy who must surely be almost himself, accompanying his father to deliver church services to a southern country parish.

The timeless land is in constant motion, as is this entire country. The Māori version of Aotearoa as waka and fish bobbing on a restless ocean is the truth of us. Inexorable forces are rolling the south up and over. Cracks and fault lines are set to jolt and send us tumbling, as mountains and coastlines and lake beds make their customary adjustments.

Then there are the changes humans inflict. The fires they set that burned the great forests of totara and beech that once clothed the hills. The sluicing that tore through topsoil to white bone. Even as this book’s predecessor was being readied for publication in 1994, the great chasm of the Clutha Gorge was vanishing beneath the rising flood of Lake Dunstan. I still avoid driving, if I possibly can, alongside its scalloped shoreline, its engineered hillsides sutured like skingraft, its waters infested with forests of weed, its columns of condensation releasing cloud into the blue skies of Central and moulds and fungi to the flushed skins of apricot or peach. Nor can I suppress the knowledge of fault lines intersecting a few kilometres below that bland surface, the landslide, the wave overtopping the dam.

In the past 25 years, other changes have risked the timeless land: wind farms, the grey suburban wash of housing development, the green flush of irrigators, the relentless erosion of species, proposals to cover its wide acres with an international airport. This is a landscape that may seem powerful, impregnable in its beauty, but it can be destroyed at the mere stroke of a bureaucratic pen. And when such places go, they leave a void in the heart. We need places to breathe, to feel ourselves expand, to experience revelation.

In this book, three great artists each exercise the technical skills built up over a long lifetime to remind us of just what it is we stand to lose. Like all art, their work says, ‘Look at this!’ Or ‘Listen to this!’ Or ‘Do you hear that?’ Or ‘Isn’t that remarkable?’ And, above all, ‘Isn’t this beautiful?’

They hand their gifts to us, and we receive them, and as we look and listen, we are brought to understand just a little more clearly who exactly it is that we are.

And where exactly it is that we live.

Landmarks Owen Marshall, Grahame Sydney, Brian Turner

A companion volume to the remarkable Timeless Land.

Buy now